Non-surgical treatment of pectus excavatum

Introduction

During last century, specific treatment of pectus excavatum (PE) in childhood and adolescents implied mainly surgical procedures. Operative techniques to correct PE were largely based on open procedures [e.g., Ravitch technique (1)] and minimally invasive techniques. In 1998, Nuss et al. reported for the first time on their 10 years experience using a new technique of minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE) (2). Today, the MIRPE technique is well established and represents the worldwide used “gold-standard” for surgical repair of PE in adolescent PE patients (3-9). However, with the widespread use of the MIRPE procedure the character and number of complications has increased (4,6-11). Moreover, numerous recent studies report on an increasing number of near fatal complications (12-16). Furthermore, in many cases of PE, the degree of pectus deformity does not immediately warrant surgery. Some patients are reluctant to undergo surgery because of the pain associated with postoperative recovery and the risk of imperfect results. In this situation, the revival and re-introduction of a conservative treatment method, the vacuum bell (VB), has made this alternative therapy for PE patients a focus of interest of patients and physicians. VB therapy represents a potential alternative to surgery in selected patients.

Conservative treatment of PE has a long tradition. The procedure of applying a vacuum to elevate the sternum was first used more than 100 years ago (17). The paediatricians Spitzy and Lange reported their experience using a glass bell to correct PE. Inadequate material and relevant side effects eliminated the routine use of this method for conservative treatment of PE. Despite the risks and unsatisfactory results after operative therapy for some patients, there has been little progress in the therapeutic use of the vacuum therapy during the last few decades. In the meantime, materials have improved and the vacuum devices can now exert strong forces. In 1992, the engineer E. Klobe, who himself suffered from a PE, developed a special device for conservative treatment of PE (18). Using his device during a period of 2.5 years, he was able to elevate the sternum and to correct his funnel chest to an extent that no funnel was visible any more (18).

Initial results using this method proved to be promising (19-21). Information on such new therapeutic modalities circulates not only among surgeons and paediatricians, but also rapidly among patients. In particular patients, who refused operative treatment by previously available procedures, now appear at the outpatient clinic and request to be considered for this method.

The vacuum bell (VB)

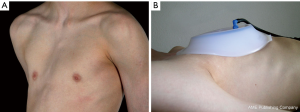

A suction cup is used to create a vacuum at the chest wall. The body of the VB is made of a silicon ring and a transparent polycarbonate window. A vacuum up to 15% below atmospheric pressure is created by the patient using a hand pump (Figure 1). Three different sizes (16 cm, 19 cm and 26 cm in diameter) exist allowing selection according to the individual patients’ age. The medium size model is available in a supplemental version with a reinforced silicon wall (type “bodybuilder”), e.g., for adult patients with a small deep PE. Additionally, a model fitted for young girls and women is available (Figure 2) (18). Pilot studies performed by Schier and Bahr (19) showed that the device lifted the sternum and ribs immediately. We could also confirm this effect by thoracoscopy during the MIRPE procedure (22). We use the VB routinely in every patient during MIRPE.

According to the user instructions and our experience, the VB should be used for a minimum of 30 minutes, twice per day, and may be used up to a maximum of several hours daily (18,20,21).

The VBs by E. Klobe are CE certified and patent registered. In USA, the device was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2012.

Indication, contraindication and side effects

Indication for conservative therapy with the VB include patients who present with mild degree of PE, who want to avoid surgical procedure and who are reluctant to undergo surgery because of pain associated with the operation. Additionally, patients’ concerns about imperfect results after surgery have to be noticed. Contraindications of the method comprise skeletal disorders, vasculopathies, coagulopathies and cardiac disorders (18,20,21). To exclude these disorders, a standardised evaluation protocol was routinely performed before beginning the therapy.

Complications and relevant side effects include subcutaneous hematoma, petechial bleeding, dorsalgia and transient paresthesia of the upper extremities during the application. Rib fractures were reported elsewhere, but never seen in our patients’ group (18,23,24).

Methods

In our unit, we offer a specialized outpatient clinic for chest wall deformities. Patients are referred by paediatricians, general practitioners or by orthopaedic surgeons. Since information on such new therapeutic modalities circulates not only among surgeons and paediatricians, but also rapidly among patients, we see an increasing number of patients who refer themselves. All patients are informed about the option of conservative vs. surgical therapy to correct PE. Standardised evaluation includes history of the patient and his family, clinical examination and photo documentation. The depth of PE is measured in a standardized supine position. Contraindications are mentioned above. To exclude cardiac anomalies, we do routinely cardiac evaluation with electrocardiogram and echocardiography before starting with the daily application.

When the patient and/or the parents decide to perform the conservative vacuum therapy, the first application of the VB occurs during the outpatient clinic visit under supervision of the attending physician. The appropriate size and model of the different type is defined. Patients learn the proper application of the device. In children under the age of 10 years, parents are instructed to use the device and children apply the VB under supervision of their parents or caregivers, respectively. The middle of the window should be positioned above the deepest point of the PE. The hand pump should be activated until the skin becomes red and/or the patient complains about local pain, respectively. Patients are in a supine position for the first application. During therapy, most adolescent and adult patients apply the device in an upright position whereas parents of children under the age of 10 years prefer to continue in a supine position. With the device in position, patients may move and walk around in their home environment.

In patients with a localized deformity, it could be helpful to apply the device using the small model (Figure 3). In patients with an asymmetric PE or a grand canon type PE, it could be useful to apply the device in changing positions.

When cardiac anomalies and other contraindications are excluded, patients may start with the daily application. All users are recommended to use the device twice daily for 30 minutes each. In fact, the length of time of daily application of the VB varies widely between patients. Some patients follow the user instructions and apply the device twice daily for 30 minutes each. However, some of the adult patients use the VB up to 8 hours daily during office hours. A group of adolescent boys apply the device every night for 7–8 hours. In our experience, the duration and frequency of daily application depends on the patients’ individual decision and motivation.

Patients undergo follow-up at 3 to 6 monthly intervals including clinical examination, measurement of depth of PE and photo documentation. Tips and tricks to optimize the application will be discussed. Clinical examination focuses on the improvement of depth of PE as well as on relevant side effects such as persistent hematoma and/or skin irritation. The endpoint of therapy is defined by the patient’s individual decision which is confirmed by clinical examination during outpatient clinic visit.

Patients and results

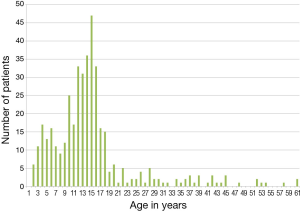

In general, the application of the VB is possible in nearby any age. Our patients group comprises applicants aged from 2 to 61 years. However, the “optimal” age for this treatment has still to be defined. The age distribution of our patients group shows that the majority of applicants are older children and young adolescents, resp (Figure 4 age distribution). Patients’ perception is different and depends on applicants’ age in many aspects. As mentioned previously, we observe age specific differences of success (18,20). During the first 1–5 applications, most of the patients experience moderate pain in the sternum and report a feeling of uncomfortable pressure within the chest. Adolescent and older patients develop moderate subcutaneous hematoma, which disappears within a few hours. Temporary side effects like transient paraesthesia of the upper extremities during the application and/or mild dorsalgia are reported by some patients. These symptoms disappear when lower atmospheric pressure will be used during application. Analgesic medication should not be necessary and is not reported from any patient and parents, respectively. As mentioned above, the application of the VB in children aged 3 to 10 years should be supervised by parents or caregivers (18,20). In this age group, no relevant side effect is reported.

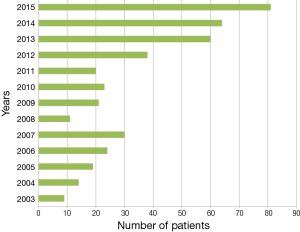

Within the last 12 years, 414 patients (80 female, 334 male) started with VB treatment at our institution (Figure 5). The median age was 16.2 years (range, 2–61 years). When starting with the application, 97/414 patients were over the age of 17 years, 80/414 over the age of 18 years. The majority of our patients are children and adolescents (Figure 4). We published a first retrospective study with preliminary results of a subset of our patients group in 2011 (23). Latest and more detailed results comprising a subset of patients were summarized in a previously published study (24).

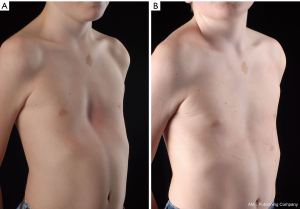

In this study, 140 patients (112 males, 28 females), aged 3 to 61 years (median 16.05 years) used the VB for 6 to maximum 69 months (average 20.5 months). When starting with the application, patients presented with a PE with depth from 1 to 6.3 cm (average 2.7 cm). Daily application of the whole group was 107.9 minutes/day (range, 10–480 minutes). Application was terminated after 20.5 months. In 61 patients, the sternum was lifted to a normal level after 21.8 months (range, 6–69 months) (Figures 6,7). The follow-up after discontinuation is 27.6 months (range, 1–73 months), and the success until today is permanent and still visible (Figures 6,7). Patients were very well motivated and compliant which is a basic precondition for a successful therapy. At follow-up, all patients were satisfied and expressed their motivation to continue the application, if necessary. In this study, 54 patients were still under treatment. However, 25/140 patients stopped the application after 15.7 months (range, 1–42 months), due to an unsatisfactory result and/or decreasing motivation. 15/25 patients underwent MIRPE.

The relevance of motivation is confirmed by the fact that 15 patients, who underwent MIRPE, used the VB for 160.6 minutes/day whereas the remaining ten patients, who stopped any kind of therapy, used the VB for 36.3 minutes/day. In three patients with asymmetric PE, the depth of PE has decreased after 9 months, but the asymmetry is still visible.

All our patients were recommended to carry on undertaking sports and physiotherapy, so that the accompanying improvement of body control was an important factor in outcome.

According to our experience based on this study group, we see three different groups of patients:

- PE-patients (children to pre-adolescent) with a mild, symmetric PE (depth <3 cm) including a still flexible chest wall; duration of treatment is expected to be 12 to 15 months;

- PE-patients (adolescents to adults) with a moderate PE (depth of PE >3 cm) and a less flexible chest wall; these patients need a close follow-up every 3 months including careful monitoring; duration of treatment is expected to be 24 to 36 months;

- PE-patients with a severe (asymmetric) PE and a stiff chest wall, presenting the first time during pubertal growth spurt; these patients represent the “risk group” for failure of the conservative treatment.

A more differentiated analysis will enable us “to see behind the curtain”. Age and gender specific differences, depth of PE, symmetry or asymmetry, concomitant malformations like scoliosis and/or kyphosis, etc. may influence the clinical course and the success of this therapy. To evaluate these different aspects, we initiated some more pilot studies (see below).

Long-term results

Long-term results including 15 years and more are still missing. Further studies are necessary to elucidate these facts.

Pre-treatment before surgery

Physicians and patients discuss about the benefit to use the VB preoperatively prior to MIRPE procedure. Since in our country the majority of patients have to pay for the device, most of our patients are not interested in this “pre-treatment”. Additionally, we observed no significant difference between patients who used the VB before surgery, and patients who underwent primary surgery (18,22-24).

Optimal age for VB therapy

As mentioned above, the optimal age for this treatment has still to be defined. We observe age specific differences of success. In our experience, growth spurt during puberty is the most important period to influence degree and depth of PE. Further studies have to evaluate whether beginning with the vacuum therapy before puberty will be more useful than starting during puberty or even later.

Costs of treatment

In most European countries, costs of treatment have to be paid by patients and parents, respectively. In some countries in South America, acquisition of the VB is covered by the individual national health care system or the local insurance.

Intraoperative use

Since 2005, we are using the device intraoperatively during the MIRPE procedure to facilitate the dissection of the transmediastinal tunnel and the advancement of the pectus introducer, the riskiest step of the MIRPE procedure. Schier and Bahr demonstrated in their pilot study that, when creating the vacuum, the elevation of the sternum is obviously (19). Therefore, we considered that the VB may also be useful in reducing the risk of injury to the heart and the mammary vessels during the MIRPE procedure. The device might also be applied for placement of the pectus bar. Since the manufacturer of the device does not have a license for sterilisation of the VB, this additional use had to be considered as “Off-label”. In agreement with our hospital hygienist and bearing in mind the nature of the material, we used gas sterilization for preparation of the device for intraoperative use.

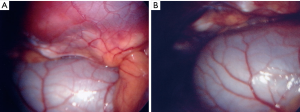

In our pilot study, 50 patients aged from 9 to 28 years (average 14.95 years; 39 males and 11 females) were included. They were operated on for PE using the MIRPE procedure. Thirty-eight patients underwent primary surgery. Twelve patients (11 male, 1 female) used the VB for a period of 4–36 months (average 19.9 months) before surgery, and discontinued the application due to decreasing motivation and/or insufficient success. The VB was applied for retrosternal dissection and advancement of the pectus introducer as well as placement and flipping of the pectus bar. The use of the VB led to a clear elevation of the sternum and this was confirmed by thoracoscopy (Figures 8,9). Advancement of the pectus introducer and placement of the pectus bar was safe, successful and without adverse events in all patients. No evidence of cardiac and/or pericardiac lesions or lesions of the mammary vessels was noted intraoperatively by using right sided thoracoscopy. Additionally, no midline incision to elevate the sternum with a hook was necessary (22).

Pilot studies evaluating the effectiveness of VB therapy

Quantitative measurement of applicated negative pressure

The success of a therapeutic procedure not only requires a good technique, but also depends on an appropriate indication. It would be useful to measure the pressure that is necessary to lift the sternum during the first application. This measurement would enable us to divide patients into different groups, to identify “perfect” patients, and allow us to predict more accurately who of the users will benefit from this method and in whom the method will not work. Since 18 months, we are using an integrated device to measure the applicated negative pressure. In a group of 148 patients (median age 13.17 years, 2 to 61 years, standard deviation ±9.0 years), the negative pressure during the first application was 0.122 bar (0.01 to 0.2 bar; standard deviation ±0.061 bar). We observed an increasing negative pressure during follow-up visits. A detailed analysis including follow-up data will be presented soon.

Objective assessment of sternal elevation in correlation to the applicated pressure

To assess the elevation of the chest wall in correlation to the applicated negative pressure, we developed an electronic device in collaboration with engineers of our technical university. Initial results proved to be promising (26). After IRB approval, we started a pilot study evaluating appropriate patients in our specialized outpatient clinic. This new device enables us to measure the sternal elevation in correlation to the applicated pressure in every patient (Figure 10). A more detailed analysis will be presented soon.

Pulmonary function (PF)

The influence of PE on PF is still discussed controversially in the literature. However, there are numerous studies which report a significant improvement of PF after surgical repair of PE. To the best of our knowledge, there is until now no data available concerning PF tests during conservative treatment of PE-patients. In collaboration with the department of paediatric pulmonology at the UKBB, we started a prospective study titled “lung function in chest wall and spine deformities—value of oscillometry techniques and longitudinal development with growth”. We will follow-up PE-patients who applicate the VB for at least 12 to 15 months.

Conclusions

The VB therapy may allow some patients with PE to avoid surgery. Especially patients with symmetric and mild PE may benefit from this procedure. The application is easy, and we noticed a good acceptance by both paediatric and adult patients. However, the time of follow-up with a maximum of 10 years is still not long enough, and further follow-up studies are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of this therapeutic tool. Additionally, more differentiated analysis must focus on age and gender specific differences. The results of ongoing studies will enable us to answer at least some of these questions. The intraoperative use of the VB during the MIRPE facilitates the introduction of the pectus bar. In any case, the method seems to be a valuable adjunct therapy in the treatment of PE.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Since this paper was conducted as a retrospective study, we did not have to have informed consent of every patient.

References

- Ravitch MM. The Operative Treatment of Pectus Excavatum. Ann Surg 1949;129:429-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, et al. A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:545-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Croitoru DP, Kelly RE Jr, Goretsky MJ, et al. Experience and modification update for the minimally invasive Nuss technique for pectus excavatum repair in 303 patients. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:437-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM, Bielek J, von Schweinitz D. Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE)--the Basel experience. Swiss Surg 2003;9:289-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hosie S, Sitkiewicz T, Petersen C, et al. Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum--the Nuss procedure. A European multicentre experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2002;12:235-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly RE, Goretsky MJ, Obermeyer R, et al. Twenty-one years of experience with minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum by the Nuss procedure in 1215 patients. Ann Surg 2010;252:1072-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park HJ, Lee SY, Lee CS. Complications associated with the Nuss procedure: analysis of risk factors and suggested measures for prevention of complications. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:391-5; discussion 391-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pilegaard HK. Nuss technique in pectus excavatum: a mono-institutional experience. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:S172-6. [PubMed]

- Sacco-Casamassima MG, Goldstein SD, Gause CD, et al. Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum: analyzing contemporary practice in 50 ACS NSQIP-pediatric institutions. Pediatr Surg Int 2015;31:493-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berberich T, Haecker FM, Kehrer B, et al. Postpericardiotomy syndrome after minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:e1-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly RE Jr, Mellins RB, Shamberger RC, et al. Multicenter study of pectus excavatum, final report: complications, static/exercise pulmonary function, and anatomic outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:1080-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barsness K, Bruny J, Janik JS, et al. Delayed near-fatal hemorrhage after Nuss bar displacement. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:e5-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Becmeur F, Ferreira CG, Haecker FM, et al. Pectus excavatum repair according to Nuss: is it safe to place a retrosternal bar by a transpleural approach, under thoracoscopic vision? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2011;21:757-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gips H, Zaitsev K, Hiss J. Cardiac perforation by a pectus bar after surgical correction of pectus excavatum: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int 2008;24:617-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM, Berberich T, Mayr J, et al. Near-fatal bleeding after transmyocardial ventricle lesion during removal of the pectus bar after the Nuss procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;138:1240-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adam LA, Meehan JJ. Erosion of the Nuss bar into the internal mammary artery 4 months after minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:394-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lange F. Thoraxdeformitäten. In: Pfaundler M, Schlossmann A, editors. Handbuch der Kinderheilkunde, Vol V. Chirurgie und Orthopädie im Kindesalter. Leipzig: FCW Vogel, 1910:157.

- Haecker FM, Martinez-Ferro M. Non-surgical treatment for pectus excavatum and carinatum. In: Kolvekar SK, Pilegaard HK, editors. Chest Wall Deformities and Corrective Procedures. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016:137-60.

- Schier F, Bahr M, Klobe E. The vacuum chest wall lifter: an innovative, nonsurgical addition to the management of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:496-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM, Mayr J. The vacuum bell for treatment of pectus excavatum: an alternative to surgical correction? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:557-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM. The Vacuum Bell for Treatment of Pectus Excavatum: an Effective Tool for Conservative Therapy. J Clin Anal Med 2011;2:1-4. [Crossref]

- Haecker FM, Sesia SB. Intraoperative use of the vacuum bell for elevating the sternum during the Nuss procedure. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2012;22:934-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM. The vacuum bell for conservative treatment of pectus excavatum: the Basle experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2011;27:623-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haecker FM, Zuppinger J, Sesia SB. Die konservative Therapie der Trichterbrust mittels Vakuumtherapie. Schweiz Med Forum 2014;14:842-49. Available online: http://www.medicalforum.ch/docs/smf/2014/45/de/smf-02088.pdf

- Haecker FM, Sesia S. Intraoperative use of the vacuum bell. Asvide 2016;3:187. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/943

- Hradetzky D, Weiss S, Häcker F-M, et al. A novel diagnostic tool for therapeutic monitoring during the treatment of pectus excavatum with the vacuum bell. Biomed Tech 2014;59:69-73.

Cite this article as: Haecker FM, Sesia S. Non-surgical treatment of pectus excavatum. J Vis Surg 2016;2:63.