Myocutaneous pedicled flap in treatment of the tuberculous bronchopleural fistula—a case report

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) still remains a global health emergency even in developed Countries, and surgical management of tuberculous empyema and lung complications may be challenging (1). Several guidelines are available, but these cannot address every possible situation. Thus, the ideal strategy of tuberculous empyema with pulmonary complications is not yet well established (2). When other treatment fails, permanent open-window thoracostomy (OWT) and thoracoplasty are the two main options, carrying different impact on the patient’s quality of life and disabilities. According to our experience, the myocutaneous pedicled flap may be considered an effective alternative for the treatment of chronic tuberculous empyema with bronchopleural fistula (BPF) avoiding permanent OWT or thoracoplasty.

Most common cases present in literature describe OWT followed by intrathoracic muscle or omental transposition [e.g., (3-6)]. Usually intrathoracic muscle transposition (IMT) is performed with latissimus dorsi muscle, serratus anterior muscle or pectoralis major muscle, seldom the rectus abdominis muscle is used [e.g., (7-9)]. In our case, the latissimus dorsi muscle was already damaged and so ipovascularized by the previous thoracotomy, and other muscles were unusable because of their thickness. Thus, we used a myocutaneous pedicled flap of the rectus abdominis muscle: it could be removed with minimal loss of function as the posterior rectus sheath was strong enough to prevent an abdominal hernia.

Case presentation

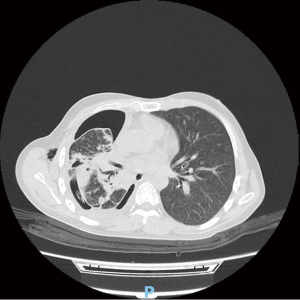

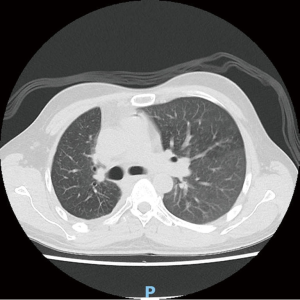

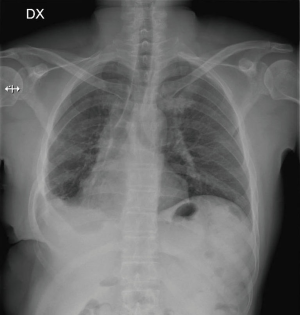

A 38-year-old male from Bangladesh, with no significant medical history in the past was admitted to our hospital for persistent haemoptysis and cough with purulent sputum in the past 3 months (Figure 1). On a physical examination, he was in poor general conditions, feverishness, underfed and complaining dyspnoea. A Thorax CT-scan showed a right hydropneumothorax associated with a 6.5 cm cavitary lesion of the right upper lobe, with many other small contralateral cavitary lesions (Figure 2). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images.

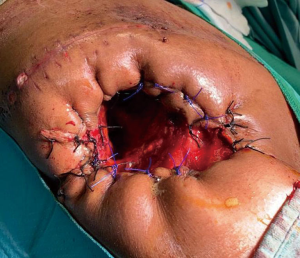

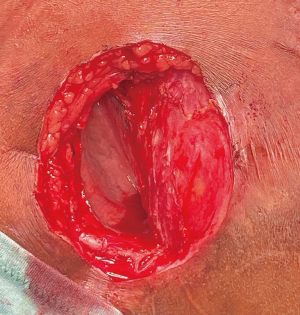

Two surgical chest drains were placed, and more than a litre of purulent fluid was removed. TB was diagnosed on the sputum sample, and an Acinetobacter superinfection was found in pleural effusion. After 6 months of proper medical treatment with Streptomycin, Isoniazid, Rifampin, and Pyrazinamide, the Thorax CT-scan showed a III stage chronic empyema (AATS guidelines) with major fibrothorax and entrapped lung, so pleural decortication was planned. Due to important parenchymal inflammatory damages, especially within the right upper and middle lobe, pulmonary decortication and surgical toilet with debridement of infected tissue were performed through a posterior thoracotomy. Postoperative period was characterized by incomplete lung re-expansion, persistent air-leaks and failure of pleural infection control with sepsis state. To avoid thoracoplasty, a very disabling procedure, we decided to proceed to an OWT with the resection of the anterolateral segments of VIII, IX and X ribs, allowing good exposure of the entire cavity and the underlying lung (Figures 3,4).

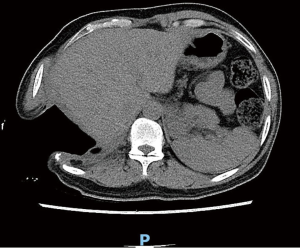

After 6 months of dressings with Rifampicin soaked gauzes applied three times a week, the Thorax CT-scan showed a significant pleural cavity reduction associated with an important improvement of the underlying lung conditions (Figure 5).

Once sufficient cleansing of the pleural cavity has been obtained, regardless of the persistence of the BPF, we decided to close the OWT with a myocutaneous pedicled flap of rectus abdominal muscle to obliterate the cavity and control the BPF (Video 1; Figure 6).

The myocutaneous pedicled flap was obtained dissecting rectus abdominal muscle at its pubic insertion, which was transposed to the thoracic cavity through a subcutaneous tunnel in order to fill the residual cavity and to close the BPF (Figure 7).

The postoperative period was completely uneventful and the patient was discharged in good general conditions, asymptomatic and without any sign of myocutaneous flap necrosis or rejection. On one month follow up, the patient remains totally asymptomatic, with a healed myocutaneous flap and without any sign of abdominal herniation.

Discussion

The management of tuberculous empyema with pulmonary complications is still challenging. In patients with signs of infection or BPF, pleural drainage could prevent septic conditions and contralateral pulmonary aspiration. In these cases, especially when BPF is present, failure rate of conservative treatments, such as close chest drainage, is very high. Often, surgical decortication and empyemectomy are not conclusive or even feasible, and disabling surgery of the chest wall should performed.

According to AATS Guidelines, in patients with chronic empyema who are medically unfit or those patients with chronic empyema with a BPF, opening a thoracic window with marsupialization of the infected thoracic cavity with resection of several ribs and dressing changes is reasonable to be performed (LOE C) (10). Our approach is a modification of the Clagett procedure, originally described by Clagett and Geraci in 1963 (11). The 2-step Clagett procedure (without flap transposition) in the treatment of post-resection empyema is possible only in the absence of BPF. In our case, OWT was carried out according to the standard technique; the entity of rib resection was as limited as possible to ensure adequate drainage and easy changes of dressings. When local control of the infection is achieved, patients are offered OWT closure. The presence of fistula is not a contraindication for closing the window. Obliteration of the cavity by transposition of the muscle flap can be reserved to patients with persistent or recurrent BPF. The type of muscle used for transposition is decided by the size and position of the cavity, local muscle flaps are used as the tissue of choice. They are generally safe, require less operative time than free flaps, can be taken as muscle with an overlying skin paddle (12). We could not use the latissimus dorsi muscle because it was damaged and so ipovascularized during the previous thoracotomy; for these reasons, we decided to use a myocutaneous pedicled flap of the rectus abdominis muscle (Figure 8).

Intrathoracic muscular transposition (IMT) is used to obliterate the pleural space and, at the same time, to close a possibly associated BPF. The use of IMT could prevent recurrent BPF, based on the stimulation of neoangiogenesis of ischemic bronchial stump and could lead to lower functional damage and to cancel the residual pleural space (9).

We can conclude that the patient’s quality of life has been significantly improved thanks to our treatment.

Conclusions

There are several studies of OWT followed by IMT in patients with chronic empyema [e.g., (12,13) and reference therein]. However, few studies have been conducted in patients with chronic tuberculous empyema (4). Our case suggests that IMT in patients with chronic tuberculosis empyema is an effective and safe procedure to close and prevent recurrent BPFs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jovs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jovs-20-61/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Nakajima Y. Open Window Thoracostomy and Muscle Flap Transposition for Thoracic Empyema. Kyobu Geka 2010;63:684-91. [PubMed]

- Shields’, General Thoracic Surgery, Wolters Kluwer, Eighth Edition, 2019.

- Regnard JF, Alifano M, Puyo P, et al. Open window thoracostomy followed by intrathoracic flap transposition in the treatment of empyema complicating pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;120:270-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JS, Park IK, Park S, et al. Treatment of Fungal Empyema Combined with Osteoradionecrosis by Thoracoplasty and Myocutaneous Flap Transposition. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;51:273-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shinohara S, Chikaishi Y, Kuwata T, et al. Flap choice for closure of open window thoracotomy: a response to the author of the article entitled "the omentum flap for empyema treatment: indications and disadvantages". J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E1777-E1779. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shinohara S, Chikaishi Y, Kuwata T, et al. Benefits of using omental pedicle flap over muscle flap for closure of open window thoracotomy. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:1697-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fricke A, Bannasch H, Klein HF, et al. Pedicled and free flaps for intrathoracic fistula management. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;52:1211-7. [PubMed]

- Pairolero PC, Arnold PG, Trastek VF, et al. Postpneumonectomy empyema. The role of intrathoracic muscle transposition. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;99:958-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold PG, Pairolero PC. Intrathoracic muscle flaps. An account of their use in the management of 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 1990;211:656-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen KR, Bribriesco A, Crabtree T, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery consensus guidelines for the management of empyema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;153:e129-e146. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clagett OT, Geraci JE. A procedure for the management of postpneumonectomy empyema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1963;45:141-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn HY, Cho JS, Kim YD, et al. Intrathoracic muscular transposition in chronic tuberculous empyema. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;61:167-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Massera F, Robustellini M, Pona CD, et al. Predictors of successful closure of open window thoracostomy for postpneumonectomy empyema. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:288-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Tuoro A, Barbarossa A, Aversa V, Puglisi A, Voci C. Myocutaneous pedicled flap in treatment of the tuberculous bronchopleural fistula—a case report. J Vis Surg 2021;7:11.