Beyond cardiac surgery: the expanded education of a false god

Medicine speaks a universal language. Commonalities of health and disease defined by the human genome transcend acquired cultural differences, produce predictable consequences, and permit the restoration of balance and harmony with the application of evidence-based restorative or curative techniques. Unique to this process is the gratification and sense of well-being enjoyed by the practitioner as well as the patient.

From the practitioner’s viewpoint, the delivery of cardiovascular surgical care requires the synthesis of multiple disciplines acting in concert to create a carefully orchestrated sequence of events that, like the notes of a symphony played by a union of diverse instruments, flow to an inevitable conclusion. From the patients’ viewpoint, though they appreciate the years of training, the hours of practice, even the inevitable failures that have brought predictability to our ministrations, they wish to be spared technical details when placing their lives in the hands of a stranger. They do not relish details of the clamping, stitching, and rummaging about their insides. Consider the feelings engendered during an interim visit to the mechanic who has disassembled a prized classic car for a repair. With assorted nuts, bolts, and springs scattered over an oil-slicked floor, the owner despairs that anyone could possibly re-assemble it. All that matters is that the car returns in a fully functional state, looking as it did when it first arrived in the repair shop. Similarly, when reading a book, no one, unless a philologist wants to wade through the cuts, pastes, and strikethroughs that result in an exquisitely turned phrase such as Helen Macdonald’s insight that “grief is love with nowhere to go”. After a performance of “The Phantom of the Opera”, I had the opportunity to see backstage how its spectacular stage effects had been achieved, but declined. Seeing the ropes and pulleys that allowed the candelabras to rise through the mist overlying the lagoon in the bowels of the Paris Opera House would have destroyed the magical effects I still retain of that scene from more than 20 years ago. Had I been a student of theater arts, I would have jumped at the opportunity. As an audience member, however, I didn’t want to know how it had been done. So it is with our patients. The frightened patient simply needs the reassurance that his/her condition has been corrected. Indeed, after the psychological and physical discomforts of a procedure have been forgotten, all that remains is the scar. As thoracic surgical pioneer Richard Overholt once said, “You have to take special care with the incision. It is all the patient will see. Your incision is your signature”.

I majored in art history in college, specializing in Chinese landscape painting of the Sung Dynasty while taking pre-medical courses. I never considered earning a living in the arts. The chance of establishing a major career in the art world by discovering a multi-million dollar purchase by a major museum to be a fake was remote. I knew that I wanted to help people in distress and ease their suffering, but had no idea whether to do it as an internist or a surgeon. Nor did I realize at the time that surgery is as much of an art form as it is a technical skill. I realized, however, that I would be spending a lifetime in the clutches of that jealous mistress, medicine, with little time for anything else. I was also aware that each patient brought a personal set of life experiences along with his illness and that I could be a better physician by being able to relate to them. I also knew that when I started down the other side of the hill and either did not want, or was unable, to engage in medical practice, that I would be better served by having something creative to fall back upon.

The humanities are in my family genes. My father was a professor of English and journalism and Vice Dean of the Annenberg School of Communications at the University of Pennsylvania. Other immediate family members have distinguished themselves in the literary and theater arts. In the family tradition, I published a medical thriller on the organ donor shortage (“The Donation”) (1), a textbook on complications in cardiac surgery (“Near Misses in Cardiac Surgery”) (2), as well as abstracts, research papers, and book chapters during a 40-year career, the latest a report on a new technique for the repair of ventricular rupture following mitral valve replacement (3). Sometime during those years, I learned how to needlepoint detailed landscapes and portraits, each piece requiring up to 160,000 stitches or more. This improved my hand-eye coordination, eliminated hesitation, and facilitated my accurate placement of stitches with a single pass. Needlepointing thus became a bridge between surgery as an art form and art itself.

Recently retired from Cardiac Surgery, I am President of the Los Angeles Doctors Symphony Orchestra. In addition, in collaboration with composer-conductor Victoria Bond (www.victoriabond.com), I have written four librettos to accompany her orchestral works, each of which is a presidential portrait similar to the “Lincoln Portrait” by Aaron Copland, three of which have been performed professionally. Already familiar with anatomy, I have studied modeling techniques with a sculptor. Finally, having been introduced to the Point Lobos State Reserve near Carmel, California, and Pfeiffer Beach in Big Sur, sites of some of the most beautiful seascapes and sandscapes in the world, I have evolved into a fine art photographer.

Surgery and photography are lonely professions. As surgeons, although we depend upon a large team of people acting in concert to achieve a desired outcome, it is a solitary, deeply personalized effort. We obsess with detail. It is not only that our procedures require magnification loupes. We obsess over the depth of a stitch, the spacing between stitches, whether or not it caught the back wall of an artery, dooming it to closure. We learn through painful experience to resist the temptation to say “it will probably be all right” if a stitch is not as perfect as possible. It is so much easier to replace a questionable stitch than spend a sleepless night worrying whether or not a patient’s artery will remain open until morning. Frequently, these are concerns known only to the surgeon. In fine art photography, there is a similar loneliness and preoccupation with detail. It involves the selection of the scene, what part of the scene upon which to focus, which lens to use, and other myriad variables such as aperture, shutter speed, “film” speed, single or rapid sequence shooting, mirror up or mirror down technique, all of which invariably require re-adjustment during a shoot. Photography also requires knowing in advance where in the sky the sun will be at a specific time in the various seasons, when it will rise or set, whether the tide will be in or out, or the moves a great blue heron will make just before taking off. A photographer not familiar with local conditions requires many tedious hours to learn such details. Photography is replete with the regret of not having waited just a little longer, or not having stopped one’s travels, to capture a fleeting instant otherwise lost forever. To avoid inconveniencing, annoying, or boring others, therefore, most of my photography trips are solitary.

It is difficult to take a bad picture in Big Sur amidst such entrancing beauty. Starting with postcard snapshots using a point-and-shoot camera, I asked myself, as scientist and artist, what imparted such beauty to these scenes? I began to crop areas of interest characterized by bright colors or unusual patterns. Graduating to more sophisticated photographic equipment (Nikon D810, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) that amplified the resolution of my images, I more clearly discerned the secrets of nature’s techniques and her palette of colors painted with broad strokes, trailing wisps, evocative veils, impressionist dabs, pointillist dots, random splashes, cubist lines, and contorted angles—what master painters had somehow discovered with their own eyes. Without powerful lenses, artists from Renoir to Rothko had identified this palette and devised transformative ways of interpreting what they saw and felt. The art of these masters were exquisite demonstrations of art imitating life. After some years, I learned to view an ordinary ocean panorama with a more educated eye. I searched for special patterns in a small area of open sea caused by vagaries of the wind, current, and waves, then captured it primarily without having to lose image quality by cropping from a larger image. In addition, I began to learn what the camera itself was going to see, for there are details seen by the camera invisible to the naked eye, even to a master painter, situated 75 yards away atop a cliff 50 feet above the water’s surface. With my camera, I discovered life imitating art. In the process, I learned not only to look, but to see.

Like surgical training, this was not a painless process (I have never forgotten breaking the purse string during my first appendectomy one sweltering August night at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, USA). I found prized images ruined by not appreciating, for example, the importance of depth of field, especially if the camera lens was not perpendicular to the subject but, rather, angled downward from a cliff top. This resulted in blurring of the foreground with a focused background, or vice versa. I learned to increase the depth of field in subsequent outings by using smaller apertures. I encountered a similar depth of field problem with macrophotography and ameliorated it by increasing the distance slightly between the camera and the subject.

Other than adding a polarizing effect to remove glare from water shots, or an occasional adjustment of black point, white balance, or exposure, I employ minimal manipulations in the digital darkroom, unless I want to create a specific “artistic” effect. “Photoshopping”, in my view, is frequently intrusive and overdone. Inserting the image of a polar bear walking down the snow-covered steps of the New York City Public Library is an inventive but obvious fabrication. While I recognize that “photoshopping” is an art form itself, such photography is as concerned with, even overwhelmed by, the shock value of the means, rather than the end itself. Like the candelabras rising through the mist from the lagoon under the Paris Opera House, I prefer to achieve an end with the means not readily apparent.

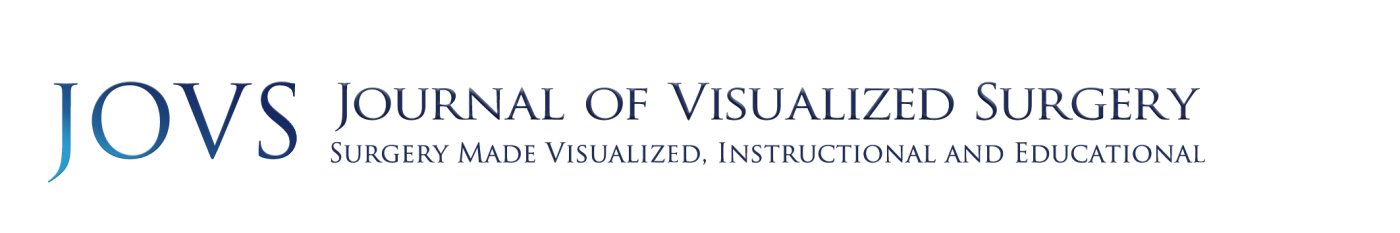

As most of my images are abstractions, I view each of them upside down, right-side up, or on either side, as a test of the integrity of the composition and the balance of the color fields. Figure 1A is an image of water in a narrow inlet with high rock walls on either side. It is dusk. The sun is to the left of the image. The black areas are shadows of rock on the swells, the white is residual sunlight on the swells, and the light green area is sand on the bottom. Rotating this image 90 degrees counterclockwise (Figure 1B), I still saw a coherent image but, struck by its resemblance to pine trees silhouetted by the Northern Lights, decided to name it “Aurora Borealis”. By receiving a name, this abstraction acquired an additional depth of significance. The beauty of the naming process is that individual viewers can interpret the same image in totally different, and equally valid, ways.

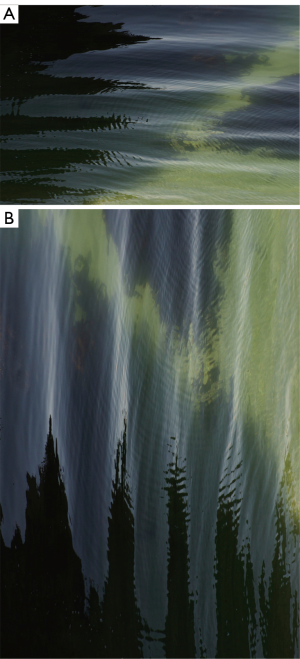

Figure 2 is an image of a small patch of open sea about 100 yards away from where I stood, 50 feet above the water’s surface. As in the previous image, there was a chill in the air as it was dusk with a gentle wind blowing. Originally taken horizontally (90 degrees clockwise from the orientation shown), when rotated to its present position I interpreted the light on the main swell to be the Milky Way and the light reflected from the kelp in the water to be stars in the universe. I entitled it “Cosmos”. An astrophotographer, looking at this image while it was on exhibit at the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, California and referring to the French astronomer Charles Messier [1730–1817], thought “M.111” a more appropriate title, a reference that would be understood only to cognoscenti aware that Messier had identified 110 major celestial objects during his career. In the astrophotographer’s eye, “Cosmos” had become Messier’s 111th.

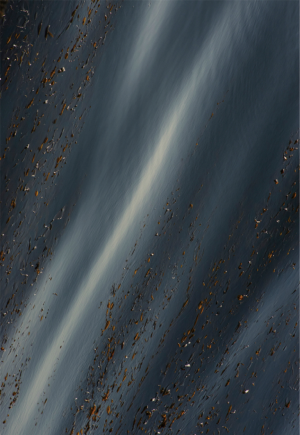

On occasion I have been unable to resist a bit of photographic manipulation for art’s sake. Figure 3 contains mirror images of a cropping taken from a larger photograph that had remarkable color and clarity, but was not a balanced composition. This image is from the same body of water seen in Figure 2 but fifty yards to the east with the sun high in the sky. The golden colors are reflections of rock walls on the opposite shore. The blue represents a deep crevice in the rock wall. Title? Perhaps “Rising Curtain”, “Falling Curtain”, or if imagined as the dessicated skull of a large animal long dead on a desert floor, “A Tribute to Georgia O’Keefe”.

Pfeiffer Beach in Big Sur, California is known as the “purple beach” because of its manganese garnet sand (purple), along with basalt (black) and quartz (off-white), all visible in Figure 4.

Waves from the Pacific Ocean continuously wash over this beach creating infinity of different patterns. On this day, the tide was partially in, and I had time to set up and capture this image mere seconds before a wave washed up and obliterated it forever. I call it “Lift-off”, a paean to space travel. Much of photography is a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

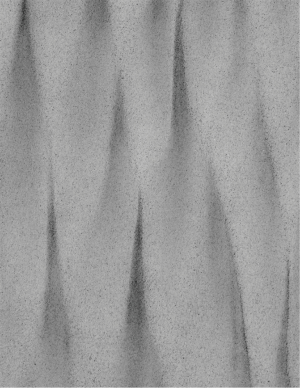

Figure 5 is another image from Pfeiffer Beach. On this day, no manganese garnet was visible, only basalt and quartz. I, therefore, rendered this image in pure black and white and called it “Sand Castles”.

There are numerous varieties of eucalyptus trees in southern California. In April, old bark detaches from the trunk to reveal the bright colors of new bark underneath. Figure 6 represents an area roughly 4 inches square on the trunk of Eucalyptus Dalrympleana, a species native to Australia. Entitled “Re-entry,” the image suggested to me a man-made object or a meteor burning up in the earth’s atmosphere, leaving a fiery trail and bits of debris in its wake.

Conclusions

Like images of expressionists or impressionists, my photography explores features of a scene that communicate its essence or life-force. Though nature does the painting, I try to see as painters did after photography obviated the need for journalistic representation, even to imagine what a painter like Monet might have done with a Nikon D810 instead of a brush. In doing so I have subordinated the reality of scenic photographs to abstractions, dominated by form, composition, balance, color, texture, and light.

This intellectualization of natural scenes produces images that provoke the viewer to assume an interpretive role, to give each image a personalized meaning, similar to the interpretive role of the photographer who decides what, and how, the camera will see. I use photography to create painterly images. Fashioned and altered by the elements, these images give permanence to the evanescent. In the process I have discovered how life imitates what we call art.

But how do the humanities relate to our work as physicians? As surgeons we spend our careers confronting realities of life and death. The patients think we are gods and wish us to be infallible, but we are only too aware of our weaknesses and shortcomings. We know we are false gods—that after the chess game the king and pawn return to the same box. The humanities provide us a necessary diversion from this harshness. We have art, Nietsche said, to save ourselves from the truth. Art is a pleasurable, even necessary, diversion from the truths we know as physicians.

But art has its own truths. The truths of artistic genius are a capacity for experimentation and perseverance, laboring under difficult emotional or physical circumstances to communicate a personalized vision of reality. The truths of my photographic efforts are that, though armed with a background knowledge of art history and the rudiments of photographic technique, it took many hikes along trails and beaches, in the wind, through sandstorms, in heat and cold, not only in the hopes of arriving in the right place at the right time but also to conjure a way to present otherwise ordinary subjects in an interpretive and personalized manner. In this sense, like Picasso’s representations of disjointed figures that express psychological turmoil or the destructiveness of war, an artist’s art is a lie. In any given instance, the artist selects only one from many techniques to render a perceived reality. So what can we conclude?

Art, whatever form it takes, provides challenge and pleasure to both the creator and the observer. But as Tolstoy observed, the “enjoyment lies in the search for the truth, not in finding it” (4). Oscar Wilde put it another way: “In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it” (5). Physicist Robert Hofstadter observed “man will never find the end of the trail” (6), or as Frankie Valli put it so poignantly in the Broadway musical, Jersey Boys, “I just keep going and going and going..chasing the music, trying to get home” (7). These epigrams apply to both artist and observer. We can conclude that life’s universal truth is the process of becoming. Life’s work, then, like a work of art, or staying abreast of the latest advances in surgery, is never finished, just abandoned for various reasons, leaving for those who follow us the fulfillment of assuming these splendid burdens themselves. In art, as in life, it is the journey that matters. Not the means. Not even the end. We are all fellow travelers on an endless journey, trying our best to get home.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Lee ME. The Donation. New York: iUniverse, 2008.

- Lee ME. Near Misses in Cardiac Surgery. New York: iUniverse, 2008.

- Lee ME, Tamboli M, Lee AW. Use of a sandwich technique to repair a left ventricular rupture after mitral valve replacement. Tex Heart Inst J 2014;41:195-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tolstoy L, Kent LJ, Berberova N. editors. Anna Karenina (Modern Library College Editions, The Modern Library). 2nd edition. New York: Random House, Inc., 1965:173.

- Wilde O. Lady Windermere's Fan in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. Boston: The Aldine Publishing Co., 1910:114.

- Hofstadter R. The Mind as Nature by Loren Eiseley. New York and Evanston: Harper and Row, 1962:45.

- Brickman M, Ellice R. Jersey Boys. 2005. Available online: www.scribd.com/doc/254317918/Jersey-Boys-Script

Cite this article as: Lee M. Beyond cardiac surgery: the expanded education of a false god. J Vis Surg 2016;2:120.