Role of thoracic endovascular aortic repair in the management of acute type B aortic dissection

Introduction

Over the last two decades, the management of acute type B aortic dissection (aTBAD) has undergone a radical paradigm shift, moving from open surgery to thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR). By covering the primary intimal tear, TEVAR eliminates antegrade flow into the false lumen (FL), expands the true lumen (TL) and reapproximates the acutely dissected layers of the aortic wall (Video 1). Over time, this process induces FL thrombosis, preventing further FL degeneration and promoting favorable aortic remodeling.

Currently, TBAD is classified according to the duration of clinical onset: hyperacute <24 hours, acute (1–14 days), subacute (15–90 days), and chronic (>90 days) (1). Acute TBAD has further been categorized as complicated or uncomplicated. Complicated aTBAD is defined by the presence of aortic rupture or organ malperfusion. In the absence of these two clinical/radiographic features, patients are considered uncomplicated. Patients presenting with complicated aTBAD represent the highest risk subgroup with an in-hospitality mortality of 31% (2). This review highlights the excellent short- and long-term outcomes of endovascular therapy for the treatment of complicated aTBAD that have established TEVAR as the standard of care for this presentation. Additionally, we discuss the evolving stratification and management of uncomplicated aTBAD patients and ongoing areas of controversy in the use of early TEVAR for these patients.

TEVAR reduces early mortality and promotes favorable long-term aortic remodeling in complicated aTBAD

Compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) and open surgery with in-hospital mortality rates of 30–35% in the latter (2), TEVAR has significantly reduced early mortality in patients presenting with complicated aTBAD. Data from our own institution and others have demonstrated low in-hospital mortality rates of 0–8% (3-5). In one of the early reports of TEVAR for complicated aTBAD, the Penn group reported a 30-day postoperative mortality rate of 2.8% and 1-year survival of 93.4% (3). The incidence of permanent renal failure (2.8%), stroke (2.8%), paraparesis (5.7%), and paralysis (2.8%) were also low in this early experience. In a later series from the Duke group, there were no cases of mortality in the 30 days following TEVAR and similar rates of renal failure, stroke, and spinal cord ischemia were reported (4). An analysis of the Emory Aortic Database of complicated aTBAD patients reported an in-hospital mortality of 5.0%, 1.3% incidence of renal failure, 7.5% incidence of stroke, 2.5% paraparesis, and no cases of paraplegia (6).

In addition to successfully treating aortic rupture and resolving malperfusion in aTBAD, TEVAR has been shown to be highly effective in remodeling the acutely dissected aorta (7). Aortic remodeling is defined as expansion of the TL, obliteration or reduction of the size of the FL by promoting FL thrombosis, and stabilization or reduction of total aortic diameter. Our analysis of aortic remodeling outcomes at Emory demonstrate that in patients who have received stenting of the entire descending thoracic aorta (DTA), complete FL thrombosis of the proximal, mid- and distal DTA can be achieved in 91%, 79% and 53% of patients at 12 months following TEVAR. No significant growth of the thoracic or abdominal aorta has been observed, although careful surveillance is warranted for the abdominal aorta, as the infrarenal FL remains perfused in 94% of patients (8). It is notable that despite the persistent FL perfusion, we have yet to re-intervene with open or endovascular therapy for abdominal aortic degeneration in patients with complete thoracic aortic coverage. These favorable aortic remodeling results have also been demonstrated by other groups (9-11). Aortic remodeling is an important feature of TEVAR, as it has been shown to significantly reduce aortic-related mortality compared to OMT (12).

One of the remaining unanswered questions with regards to TEVAR for complicated aTBAD is the optimal procedure to perform. Initially, TEVAR with <20 cm coverage of the DTA was performed due to concerns for spinal cord ischemia with aortic coverage >20 cm (13). Recently, we analyzed outcomes from the Emory Aortic Database comparing aTBAD patients with short segment or “standard” aortic coverage to patients undergoing “extended” coverage from the left subclavian artery to the level of the celiac axis with covered stents (mean length of aorta coverage: 241.7±29.2 mm vs. standard: 180.8±22.3 mm, P<0.001) (8). The goal of extensive aortic endograft coverage is to maximize the aortic remodeling benefits by covering all secondary tears in the DTA, thus further reducing both antegrade and retrograde perfusion of the FL. Our analysis demonstrated that extended TEVAR can be performed safely with a low risk of spinal cord ischemia using a strategy of selective lumbar drain use and permissive hypertension. Furthermore, extended TEVAR provided superior remodeling as 53% of extended patients had complete FL thrombosis or obliteration at the level of the diaphragm compared to only 16% in the standard group (P=0.004) This translated into a greater freedom from distal aortic reinterventions with extended TEVAR at 5-year follow-up (extended 92% vs. standard 68%, P=0.04) (8).

An alternative to the extended TEVAR technique is the PETTICOAT procedure which involves endo-grafting of the proximal and mid-DTA with covered stent grafts, followed by bare metal stents extending throughout the entire thoracic and abdominal aorta. This technique was developed to improve aortic remodeling while mitigating the risk of spinal cord ischemia. Multiple studies have demonstrated low mortality and favorable aortic remodeling outcomes with approximately 50% of patients achieving complete FL thrombosis of the DTA with the PETTICOAT technique (9-11). In an effort to completely obliterate the FL and achieve a “uni-luminal” repair, the Stent-Assisted Balloon-Induced Intimal Disruption and Relamination in Aortic Dissection Repair (STABILISE) technique was designed. This technique consists of deployment of covered stent grafts from the left subclavian artery to the diaphragm followed by bare metal stenting to the aorto-iliac bifurcation. An aortic balloon is then inserted and expanded inside the covered stent grafted segment of the distal DTA with the intent of rupturing the dissection flap and re-opposing the intimal flap to the aortic wall. Aortoplasty is performed throughout the entire bare metal segment in an effort to achieve a single lumen at the aorto-iliac bifurcation (14). This technique has demonstrated low rates of adverse events at 30 days: 2% death, 0% stroke, and 5% SCI, as well as excellent aortic remodeling outcomes. In an analysis of 41 aTBAD patients undergoing STABILISE with a median follow-up of 12 months, 100% achieved complete elimination of FL perfusion throughout the stented segments of the thoracoabdominal aorta (15).

Regardless of the strategy is chosen, however, retrograde FL perfusion distal to the stent graft remains the biggest hurdle to overcome in the use of TEVAR for aTBAD, and thus, the abdominal aorta remains at risk for further expansion. Nevertheless, the advantage of TEVAR over open surgery or OMT is indisputable, and reflected by the Class I indication as the treatment of choice for complicated aTBAD in the most recent version of the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines (16).

Management of uncomplicated TBAD: evolving role of TEVAR and ongoing areas of controversy

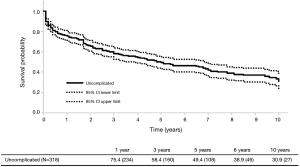

In contrast to complicated aTBADs, the optimal therapy for uncomplicated aTBADs remains controversial. Traditionally, OMT has been the primary therapy for uncomplicated aTBAD with surgical intervention (open or endovascular) reserved for the development of aneurysmal degeneration of the FL in the chronic phase. In a large meta-analysis containing 1,548 patients with uncomplicated aTBAD, OMT resulted in a 93.6% survival to hospital discharge (17). However, as patients enter the chronic phase with OMT, the need for intervention rises with a corresponding reduction in survival. Historical and contemporary data have demonstrated a 25–30% incidence of open surgical intervention in the chronic phase for medically managed patients with aTBAD (18-21). Furthermore, recent natural history TBAD data have demonstrated long-term survival rates of 48–59% with OMT and overall intervention-free survival rates of <50% (18,22). Given these data, we examined our own institutional experience in managing uncomplicated aTBAD at Emory. In our analysis of 318 patients presenting with uncomplicated aTBAD managed with OMT from 2000 to 2016, 46% of patients required either open or endovascular intervention at a mean of 2.7 years after their initial diagnosis of aTBAD. Of the entire cohort, the intervention-free survival was 30.9% and the overall survival was 58.9% at 10 years (6) (Figure 1).

In light of the realization that OMT leads to poor long-term outcomes in uncomplicated aTBAD combined with the excellent outcomes reported with TEVAR in complicated aTBAD, the case has been made to treat all aTBADs with TEVAR. Unfortunately, there is a lack of robust data regarding the efficacy of TEVAR in uncomplicated aTBAD, and the data that currently exists is limited by its retrospective nature. Currently, there is only one existing prospective randomized trial comparing OMT to TEVAR for the treatment of uncomplicated aTBAD, the Acute Dissection Stent-grafting OR Best Medical Treatment (ADSORB) trial. ADSORB randomized patients with uncomplicated a TBAD to OMT (n=31) or OMT + TEVAR (n=30) and demonstrated improved aortic remodeling but no difference in mortality with TEVAR at 1 year (23).

Although limited by their retrospective nature, there are several notable studies describing the use of TEVAR in uncomplicated aTBAD in the literature from which lessons can be learned. Yong-Lin and colleagues analyzed their experience with the treatment of 338 patients (TEVAR n=184 vs. OMT n=154) presenting with uncomplicated aTBAD from 2003-2014. At 30 days, there was no difference in stroke, organ failure or mortality between the two groups. At 5-year, the freedom from aortic-related adverse events was improved with TEVAR (TEVAR 71.8% vs. OMT 62.2%, p=0.03) and all-cause mortality was reduced with TEVAR (TEVAR 10.8% vs. OMT 14.3%, P=0.01) (24). In a similar study, Xiang and colleagues compared 357 patients from 2008-2018 who were treated with either OMT (n=166) or TEVAR (n=191). After propensity-score matching was performed, 145 match pairs were analyzed. Their results demonstrated no significant difference in stroke, acute renal failure, retrograde type A dissection or 30-day mortality between the two treatment arms. However, at 5-year, the freedom from all-cause mortality (TEVAR 91.9% vs. OMT 82.2%, P=0.28) and aortic-related mortality (TEVAR 94.1% vs. 86.1%, P=0.44) was significantly improved in the TEVAR group. In the multi-variable analysis, OMT was identified as a significant risk factor for all-cause mortality (25). Finally, Iannuzzi and colleagues analyzed outcomes of 9,165 patients from the California Office of Statewide Hospital Planning Development Database presenting with uncomplicated aTBAD from 2000 to 2010. Patients were treated with either OMT (n=8,717) TEVAR (n=266) or open surgery (n=182). There was no significant difference in inpatient mortality between TEVAR and OMT. However improved survival was observed with TEVAR at 1-year (TEVAR 85% vs. OMT 76%, P<0.01) and 5-year (TEVAR 76% vs. OMT 60%, P<0.01) follow-up (26).

In a statement from the 2008 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Expert Consensus Document on the Treatment of Descending Thoracic Aortic Disease Using Endovascular Stent-Grafts, the authors stated that “in patients with uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection, (medical management) constitutes a benchmark that will be difficult to surpass or even match by endovascular stent-graft treatment…” (27). Although this may have been true in 2008, contemporary data from our group and others at high volume aortic centers have demonstrated equivalent or superior short-term outcomes with TEVAR compared to OMT for the treatment of both uncomplicated and complicated (higher risk cohort) aTBAD (4-6,12). Therefore, despite the lack of a robust randomized controlled trial, there is growing data and support from the aortic community that TEVAR may improve long-term outcomes compared to OMT in patients with uncomplicated aTBAD.

Are there high-risk features in uncomplicated aTBAD that warrant early TEVAR?

The data discussed in the preceding paragraphs have clearly demonstrated that a significant number of patients with uncomplicated aTBAD will ultimately fail OMT and require intervention due to FL degeneration. Furthermore, TEVAR has been shown to be highly effective in inducing aortic remodeling which reduces aortic-related mortality in the chronic phase of TBAD. Yet, TEVAR is not a risk-free procedure, and carries peri-procedural risks of retrograde type A dissection, stroke, spinal cord ischemia, vascular injury and acute kidney injury. Therefore, rather than stenting all uncomplicated aTBADs, the optimal approach would be to identify those patients with a high probability of OMT failure at the time of their initial diagnosis and intervene in the acute phase with TEVAR. Our group has demonstrated that endovascular therapy has a greater impact on aortic remodeling and long-term survival when TEVAR is performed early in the disease process. Endovascular therapy is more effective in expanding the TL and obliterating the FL in the acute phase when the dissection membrane is thin and pliable, as opposed to in the chronic phase when it becomes a more fibrotic, thickened, rigid structure (6).

Therefore, investigations have been performed to identify “high-risk” radiographic features in the acute phase that may predict FL aneurysm formation in the chronic phase. These investigations have primarily focused on three anatomic features: aortic diameter, FL size and thrombosis status, and morphologic characteristics of the primary intimal tear. In an analysis of 254 patients receiving OMT for TBAD, Schwartz et al. found an aortic size of 4.0 cm to be predictive of intervention (28). This finding was corroborated by other studies demonstrating that a DTA diameter of >4.0 cm is predictive of aortic growth and adverse outcomes in the chronic phase of TBAD (29-33). Our own institutional analysis of predictors of OMT failure among uncomplicated aTBAD found a DTA aortic size cutoff of >4.5 cm at time of presentation to be the most important predictor, manifesting as both an increased risk of aortic intervention and reduced long-term survival (HR 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24–1.56), compared to those presenting with a smaller DTA (34). This data is intuitive, as patients who have an aneurysmal aorta (≥4.0 cm) at time of their dissection will have a greater likelihood of either aortic rupture, or need for intervention in the chronic phase as the FL degenerates.

In contrast, the FL data is ambiguous and conflicting. It is well-recognized that patients with complete FL thrombosis have improved survival, whereas those with a completely patent FL have an increased risk of aneurysm formation and death (35-37). However, the implications of a partially thrombosed FL are unclear. In an International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection study, Tsai and colleagues analyzed 201 patients with aTBAD (including 27% complicated aTBAD treated with open or endovascular therapy) with a median follow-up of 2.8 years. In this study, the status of the FL was patent in 57% and partially thrombosed in 34% of patients, and partial FL thrombosis was found to be an independent predictor of mortality (HR 2.69, 95% CI: 1.45–4.98, P=0.002) (35). However, in our own institutional study consisting of 318 uncomplicated aTBADs, partial FL thrombosis was not identified as an independent predictor of OMT failure (34). Additionally, a FL diameter of >22 mm and the location of the FL on the greater curve of the aorta have also been shown to be predictive of aneurysm growth (38-40). Studies attempting to characterize the primary intimal tear have suggested that size ≥10 mm or location in close proximity to the left subclavian artery in Zone 3 are independent predictors of aneurysm formation (28,40).

Despite this progress, there is no single radiographic feature that reliably predicts aortic growth and death. This underscores the overall lack of understanding of aTBAD anatomy and physiology that prevents accurate prediction of which patients will have complications requiring intervention and which will be adequately treated with OMT alone. At Emory, we consider an uncomplicated aTBAD “high risk” if they have a combination of the following features: (I) intractable pain or hypertension; (II) total aortic diameter >4.0 cm; (III) FL diameter >22 mm; (IV) primary intimal tear location in Zone 3. In this cohort of patients, we are aggressive about performing TEVAR in the acute phase.

Conclusions

Over a decade of experience of using TEVAR in the treatment of patients with complicated aTBAD has led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of complicated aTBAD, and TEVAR is now the standard of care in this high-risk presentation. Moreover, there is extensive evidence that early TEVAR remodels the aorta and improves late aortic-specific survival. However, it is not without periprocedural risks, and the risk of retrograde type A dissection and neurological complications remain concerning. Evidence is mounting that demonstrates the inadequacy of OMT in the management of uncomplicated aTBAD. Uncomplicated aTBAD remains a heterogenous disease process with some patients having higher risk features that may benefit from early TEVAR. The next steps will be to develop a predictive model to determine which patients can benefit from early endovascular therapies to remodel the aorta and prevent late complications.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Ibrahim Sultan and George Arnaoutakis) for the series “Advancement in the Surgical Treatment of Aortic Dissection” published in Journal of Visualized Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jovs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jovs-20-109/coif). The series “Advancement in the Surgical Treatment of Aortic Dissection” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg 2020;71:723-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): New insights into an old disease. JAMA 2000;283:897-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szeto WY, McGarvey M, Pochettino A, et al. Results of a new surgical paradigm: endovascular repair for acute complicated type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:87-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hanna JM, Andersen ND, Ganapathi AM, et al. Five-year results for endovascular repair of acute complicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2014;59:96-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bavaria JE, Brinkman WT, Hughes GC, et al. Outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair in acute type B aortic dissection: results from the Valiant United States Investigational Device Exemption Study. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:802-8; discussion 808-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lou X, Chen EP, Duwayri YM, et al. The impact of thoracic endovascular aortic repair on long-term survival in type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;105:31-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leshnower BG, Duwayri YM, Chen EP, et al. Aortic remodeling after endovascular repair of complicated acute type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:1878-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lou X, Duwayri YM, Jordan WD, et al. The safety and efficacy of extended TEVAR in acute type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sultan I, Dufendach K, Kilic A, et al. Bare metal stent use in type B aortic dissection may offer positive remodeling for the distal aorta. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:1364-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lombardi JV, Cambria RP, Nienaber CA, et al. Aortic remodeling after endovascular treatment of complicated type B aortic dissection with the use of a composite device design. J Vasc Surg 2014;59:1544-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sobocinski J, Lombardi JV, Dias NV, et al. Volume analysis of true and false lumens in acute complicated type B aortic dissections after thoracic endovascular aortic repair with stent grafts alone or with a composite device design. J Vasc Surg 2016;63:1216-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nienaber CA, Kische S, Rousseau H, et al. Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection:long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:407-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feezor RJ, Martin TD, Hessjr PJ, et al. Extent of aortic coverage and incidence of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:1809-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hofferberth SC, Nixon IK, Boston RC, et al. Stent-assisted balloon-induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair: the STABILISE concept. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:1240-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faure EM, Batti SE, Rjeili MA, et al. Mid-term outcomes of stent-assisted balloon induced disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair (STABILISE) in acute type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;56:209-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tadros RO, Tang GHL, Barnes HJ, et al. Optimal Treatment of Uncomplicated Type B Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1494-504. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fattori R, Montgomery D, Lovato L, et al. Survival after endovascular therapy in patients with type B aortic dissection: a report from the International Registry of Acute Aoritc Dissection (IRAD). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:876-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durham CA, Cambria RP, Wang LJ, et al. The natural history of medically managed acute type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2015;61:1192-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charilaou P, Ziganshin BA, Peterss S, et al. Current Experience with Acute Type B Aortic Dissection: Validity of the Complication-Specific Approach in the Present Era. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:936-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juvonen T, Ergin MA, Galla JD, et al. Risk factors for rupture of chronic type B dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117:776-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gysi J, Schaffner T, Mohacsi P, et al. Early and late outcome of operated and non-operated acute dissection of the descending aorta. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;11:1163-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsai TT, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, et al. Long-Term Survival in Patients Presenting With Type B Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation 2006;114:2226-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunkwall J, Kasprzak P, Verhoeven E, et al. Endovascular Repair of Acute Uncomplicated Aortic Type B Dissection Promotes Aortic Remodeling: 1 Year Results of the ADSORB Trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014;48:285-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qin YL, Wang F, Li TX, et al. Endovascular repair compared with medical management of patients with uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. JACC 2016;67:2835-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang D, Kan X, Liang H, et al. Comparison of mid-term outcomes of endovascular repair and medical management in patients with acute uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iannuzzi JC, Stapleton SM, Bababekov YJ, et al. Favorable impact of thoracic endovascular aortic repair on survival of patients with acute uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2018;68:1649-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Svensson LG, Kouchoukos NT, Miller DC, et al. Expert consensus document on the treatment of descending thoracic aortic disease using endovascular stent-grafts. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:S1-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwartz SI, Durham C, Clouse D, et al. Predictors of late aortic intervention in patients with medically treated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2018;67:78-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onitsuka S, Akashi H, Tayama K, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic predictors of medically treated acute type B aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:1268-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marui A, Mochizuki T, Koyama T, et al. Degree of fusiform dilatation of the proximal descending aorta in type B acute aortic dissection can predict late aortic events. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:1163-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grommes J, Greiner A, Bendermacher B, et al. Risk factors for mortality and failure of conservative treatment after aortic type B dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:2155-60.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Bogerijen GH, Tolenaar JL, Rampoldi V, et al. Predictors of aortic growth in uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2014;59:1134-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueki C, Sakaguchi G, Shimamoto T, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:767-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lou X, Duwayri YM, Chen EP, et al. Predictors of failure of medical management in uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:493-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsai TT, Evangelista A, Nienaber CA, et al. Partial thrombosis of the false lumen in patients with acute type B aortic dissection. N Engl J Med 2007;357:349-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Hayashi K, et al. Growth rate of aortic diameter in patients with type B aortic dissection during the chronic phase. Circulation 2004;110:II256-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernard Y, Zimmermann H, Chocron S, et al. False lumen patency as a predictor of late outcome in aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1378-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song JM, Kim SD, Kim JH, et al. Long-term predictors of descending aorta aneurysmal change in patients with aortic dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:799-804. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ray HM, Durham CA, Ocazionez D, et al. Predictors of intervention and mortality in patients with uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2016;64:1560-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Codner JA, Lou X, Duwayri YM, et al. Primary tear distance from left subclavian artery predicts growth in chronic type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2018;67:e8. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Lou X, Leshnower BG. Role of thoracic endovascular aortic repair in the management of acute type B aortic dissection. J Vis Surg 2021;7:45.