Carcinoid heart disease and a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor

Introduction

Primary ovarian carcinoid tumors account for less than 0.5% of all carcinoid tumors (1). Patients with primary ovarian carcinoid tumors may develop carcinoid heart disease by release of bioactive amines directly into the inferior vena cava or renal vein. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by flushing, secretory diarrhea and bronchospasm. Half of patients with carcinoid syndrome exhibit carcinoid heart disease and subsequent right-sided valvular dysfunction and right ventricular failure (1). Valve replacement is performed to relieve symptoms and improve survival (2). We describe a case of a 55-year-old female who presented with carcinoid heart disease from a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor and underwent pulmonary and tricuspid valve replacements and patch enlargement of the right ventricular outflow tract.

Case presentation

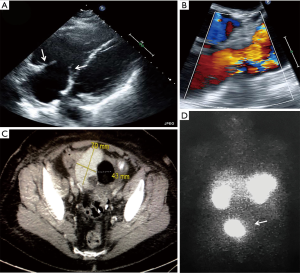

A 55-year-old female presented with worsening dyspnea on exertion, flushing and lower extremity edema. Auscultation revealed a holosystolic murmur at the left lower parasternal border. Chromogranin A and 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels were elevated. On transesophageal echocardiography, severe tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation was noted. The tricuspid valve leaflets were thickened and severely restricted with failure of coaptation and visible plaques (Figures 1,2A). There was also a mixed pattern of pulmonary regurgitation and stenosis (Figure 2B). Computed tomography and octreotide scans demonstrated an 8.2×7×4.3 cm solid enhancing mass emanating from the right pelvis (Figure 2C,D). Carcinoid heart disease arising from a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor was suspected. Because of the severity of the patient’s symptoms, a decision was made to replace her tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

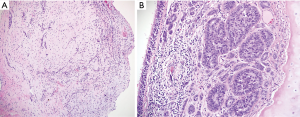

Intravenous infusion of octreotide was initiated the day of the operation. The pulmonary valve was approached through a longitudinal incision across the valve annulus onto the outflow portion of the right ventricle. White plaques were adherent to the fibrotic pulmonary valve leaflets (Figure 3A). Chordae were also fused and deformed. A patch enlargement of the right ventricular outflow tract was performed to accommodate an adequately sized Edwards pericardial valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). Through a right atriotomy, the tricuspid valve was exposed. Fibrosis and fusion of the tricuspid valve leaflets and subvalvular apparatus were noted. The leaflets were excised and the tricuspid valve was replaced with a Medtronic porcine valve (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The patient was discharged on POD#10 on monthly long-acting octreotide therapy.

The patient underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 3 months later. Pathology revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of the right ovary (Figure 3B). At 1-year follow-up, the patient is alive without evidence of disease and normal tumor marker levels.

Conclusions

The incidence of valvular heart disease approaches 30% in the case of primary ovarian carcinoid tumors. Elevated bioactive amines levels released from carcinoid tumors promote severe endocardial plaque formation resulting in most commonly, right-sided valve destruction and ensuing right-sided heart failure (1).

Right ventricular failure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with carcinoid heart disease (4-6). It has been recommended that patients with even mild symptoms undergo valve surgery to prevent progression of right ventricular dysfunction. Although operative mortality approaches 20%, valve replacement results in improved midterm outcomes (2). Traditionally, mechanical prostheses have been favored secondary to potential valve degeneration from high circulating serotonin (2,4). Nonetheless, contemporary data suggest bioprosthetic valves are durable and avoid the higher risks of thrombosis and bleeding associated with mechanical prostheses (2).

Primary ovarian carcinoid with carcinoid heart disease should be considered in a symptomatic female patient with a pelvic tumor, isolated right-sided valve disease and elevated tumor markers. Surgery is necessary to provide long-term functional improvement and prolonged survival.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jovs.2019.01.10). KAP serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Visualized Surgery from Jun 2018 to May 2020. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chaowalit N, Connolly HM, Schaff HV, et al. Carcinoid heart disease associated with primary ovarian carcinoid tumor. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1314-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya S, Raja SG, Toumpanakis C, et al. Outcomes, risks and complications of cardiac surgery for carcinoid heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:168-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah VN, Orlov OI, Plestis KA. Carcinoid heart disease and a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor. Asvide 2019;6:130. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/31640

- Castillo JG, Milla F, Adams DH. Surgical management of carcinoid heart valve disease. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;24:254-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mokhles P, van Herwerden LA, de Jong PL, et al. Carcinoid heart disease: outcomes after surgical valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:1278-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pellikka PA, Tajik AJ, Khandheria BK, et al. Carcinoid heart disease. Clinical and echocardiographic spectrum in 74 patients. Circulation 1993;87:1188-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Shah VN, Orlov OI, Plestis KA. Carcinoid heart disease and a primary ovarian carcinoid tumor. J Vis Surg 2019;5:48.