Thoracoscopic anterior segmentectomy of the right upper lobe (S3)

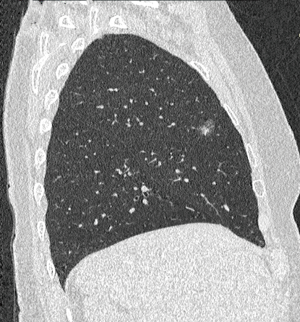

S3 segmentectomy can be indicated for solitary metastases, cT1a non-small cell lung carcinomas and ground glass opacities (Figure 1). At first sight, it looks as a challenging procedure as the anatomy of vascular elements is complex, the segment is comprised between S1 and the middle lobe and, in addition, the minor fissure is most often fused. A sufficient exposure of the bronchial trifurcation must be achieved. Creating a tunnel between S3 and the middle lobe greatly eases dissection of the vessels.

Anatomical landmarks

Bronchi

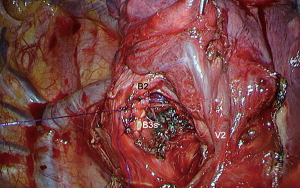

B3 is the anterior branch of the upper bronchus. In 14% of the cases, it is independent from the apicoposterior truncus (B1+2), and in 40% of the cases it is a branch of a trifurcation B1-B2-B3 (1). It is usually easily recognized by its anterior direction, while B1 and B2 have a cephalad direction. Lymph nodes are frequently found at the origin of B3. Even for benign conditions, removal of these nodes is required for an optimal disclosure of the B3 root.

Arteries

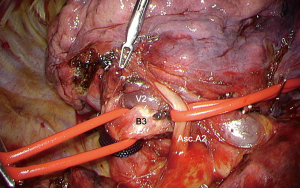

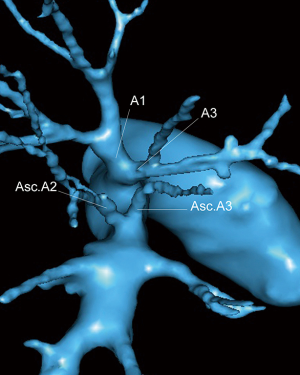

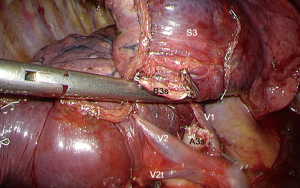

A3 is the lowermost branch of the truncus anterior. In 48% of the cases, S3 receives its 2 branches (A3a and A3b) from the truncus anterior (TA). In the other cases, there is also an ascending A3 artery from the arterial truncus intermedius (TI) which raises close to the ascending A2 and is recognized from its anterior direction (Figure 2).

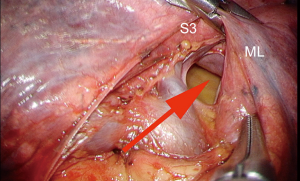

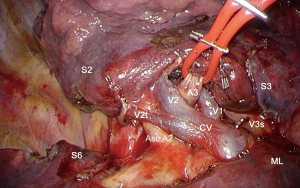

Veins

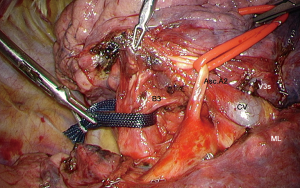

Variations of the venous pattern are numerous (2). There are two types of veins: (I) a large V3 that is the lowermost branch of the central vein and (II) 1 or 2 small ascending veins branching from the central vein that are easily recognized as they come directly from the anterior segment (Figure 3).

Technique

We used a fissure-based technique and multiple ports access, as described by our team (3) and by others (4). The anterior portion of the major fissure, between S3 and the middle lobe is usually fused, or even inexistent. First opening of this fissure is the key for an easy vascular dissection. When incomplete, the fissure can be opened by a tunnel technique, as follows:

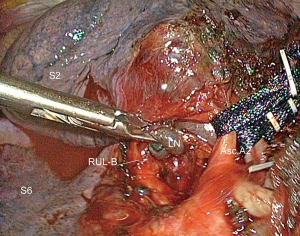

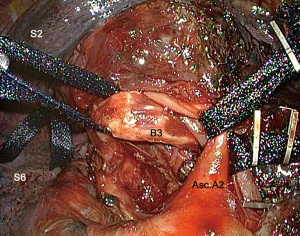

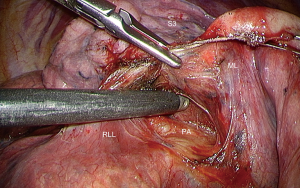

The fissure is opened at the junction of the transverse and oblique fissures as for an apicoposterior segmentectomy. Once Asc.A2—and Asc.A3 if present—is identified, the edge of the middle lobe is lifted up and a path is created with a blunt tip dissector and/or an endo-peanut, keeping close to the vessels (Figure 4). The course is pursued in an anterior direction (Figure 5). The upper and middle lobes are then retracted backward to expose the upper vein in a usual manner, so that the middle lobe vein and V3 are clearly seen. In a second step, the hilum is exposed and a path is done with a dissector between the venous branches and an endo-peanut permits dissection in a posterior direction. The instrument is gently manoeuvred and pushed so that it meets up with the already dissected posterior opening of the fissure. A curved tip 60 mm endostapler can then be inserted in the tunnel and fired. The middle lobe and S3 are now separated, giving access to the vessels. Figure 6 illustrates a rather straightforward case with a thin and short fissure (Figure 6) and Figure 7 demonstrates a more difficult case with a thick and long fissure (Figure 7).

Control of the B3 bronchus requires a large exposure of the upper lobe bronchus so that a sufficient retraction of the segmental bronchi can be exerted. The posterior aspect of the fissure is opened as for an upper lobectomy, in order to expose the ascending A2 (Asc.A2) and the bronchus (Figure 8). Once these two elements have been dissected, both are looped (Figure 9). The upper lobe bronchus is then retracted backward and the Asc.A2 forward, thus exposing B3. Lymph nodes are frequently present at the origin of B3 (Figure 10) (1,3). They are dissected and removed (Figure 11). If the patient is operated on for a malignant disease, these nodes are sent for frozen section. If positive, the procedure should be transformed into a lobectomy (8). B3 is dissected, taped and then stapled (Figures 12,13). In some patients, even after an extensive dissection, the space is very limited and does not permit passage of a stapler, even with a curved tip. In these cases, B3 must be cut with a scalpel blade and its stump sutured (Figures 14,15).

The large central vein runs in an anteroposterior direction. The two most anterior tributaries, V3a and V3b, drain S3. These are clipped and dissection of the central vein and V3 is pursued (Figure 16).

Dissection of the veins helps exposing A3 artery whose 2 branches are dissected (Figure 17) and then clipped or stapled (Figure 16).

As the fissure has already been opened at the beginning of the procedure, S3 is now fully mobile and the intersegmental plane S2–S3 can be divided, according to the predetermined demarcation line, whatever the method used. We favor near-infrared imaging with systemic injection of indocyanine green (12). The stump of B3 is gently pushed away using blunt dissection, so that it cannot be caught into the staple line. A large clamp is applied on the intersegmental plane to compress the parenchyma and ease application of the stapler (Figures 18,19). The viability of the remaining segments 1 and 2 is checked by reventilation (Figure 20).

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Alessandro Brunelli) for the series “Uncommon Segmentectomies” published in Journal of Visualized Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The series “Uncommon Segmentectomies” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. DG is consultant for an instrument manufacturer (Delacroix Chevalier). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Nomori H, Okada M. Illustrated anatomical Segmentectomy for Lung Cancer. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag, 2012.

- Shimizu K, Nagashima T, Ohtaki Y, et al. Analysis of the variation pattern in right upper pulmonary veins and establishment of simplified vein models for anatomical segmentectomy. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;64:604-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gossot D. Atlas of endoscopic major pulmonary resections. 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, 2018:180.

- Oizumi H, Kato H, Endoh M, et al. Port-access thoracoscopic anatomical right anterior segmentectomy. J Vis Surg 2015;1:16. [PubMed]

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Creating a tunnel for separation of S3 from the middle lobe in a patient with a thin minor fissure. Asvide 2018;5:719. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26799

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Creating a tunnel for separation of S3 from the middle lobe in a patient with a thick minor fissure. Asvide 2018;5:720. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26801

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Opening of the posterior part of the major fissure for better exposure of the segmental bronchi. Asvide 2018;5:721. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26802

- Gossot D, Lutz JA, Grigoroiu M, et al. Unplanned Procedures During Thoracoscopic Segmentectomies. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:1710-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Dissection and stapling B3. Asvide 2018;5:722. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26805

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Manual division of B3 because of insufficient room for stapling. Asvide 2018;5:723. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26806

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Dissection and control of A3. Asvide 2018;5:724. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26807

- Guigard S, Triponez F, Bédat B, et al. Usefulness of near-infrared angiography for identifying the intersegmental plane and vascular supply during video-assisted thoracoscopic segmentectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;25:703-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Delineation of the intersegmental plane using systemic injection of indocyanine green under near-infrared imaging and division of the plane. Asvide 2018;5:725. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26808

- Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Reventilation of segments 1 and 2. Asvide 2018;5:726. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/26809

Cite this article as: Lutz J, Seguin-Givelet A, Gossot D. Thoracoscopic anterior segmentectomy of the right upper lobe (S3). J Vis Surg 2018;4:183.