Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery for esophageal cancer

Minimally invasive (MI) esophageal mobilization for esophageal cancer is being performed for over two decades now. The technique was applied as a part of modified McKeown esophagectomy, which ended up with laparotomy and left cervical esophagogastrostomy (1). This technique is still used for tumors located at the level or higher than the carina. However in recent years, due to the disadvantages of a neck anastomosis (higher leak, stricture and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury rate), MI Ivor Lewis esophagectomy using a high thoracic anastomosis gained popularity (2). This was also evident in the practice of Dr. Luketich with a lower mortality (<2%) and leak (<5%) rate following a change of practice to MI Ivor Lewis esophagectomy (3).

Classical video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) approach to esophageal cancer uses four incisions (4). The rationale for these incisions is to provide ease for anteroposterior movement of esophagus, angles for instruments and suturing especially during placement of a purse-string suture to esophagus for preparation of an intrathoracic anastomosis with circular stapler (4).

Uniportal VATS (U-VATS) presents a challenge for esophageal surgeons, as you have to do the same surgery from a single 3–5 cm incision. In this article we will describe the peculiarities of a uniportal approach for esophageal cancer.

U-VATS for esophageal mobilization

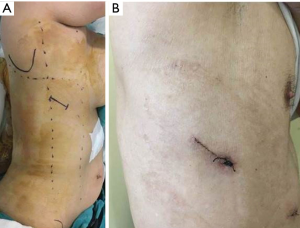

A left sided double lumen tube intubation is performed and then the patient is positioned in a left lateral decubitus position with 30 degrees tilting to the anterior side. The incision is placed either at the 5th or 6th intercostal space close to the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). The incision is placed on the 6th intercostal space if you have long endoscopic instruments or the patient has a smaller chest in the superoinferior axis. Otherwise 5th intercostal space provides access to the upper and lower chest cavity and mediastinum.

The chest is explored for adhesions, pleural implants or obvious lung metastasis. The lower lobe is grasped and retracted anterosuperiorly with a ring forceps. The retracting ring forceps is typically at the apex of the incision, while the camera in the middle and energy device in the bottom part. The first move is to divide the inferior pulmonary ligament completely and lift station 9 lymph nodes to the esophagus. At this stage a forceps with a peanut just under the retracting forceps helps to lift the lung tissue and obviate the dissection plane. Then mediastinal pleura is incised close to the lung parenchyma over the inferior pulmonary vein and intermediary bronchus to the level of the azygos vein. The dissection is then advanced close to the azygos vein posteriorly and mediastinal pleura is incised until the hiatus anterior to the hemiazygos vein.

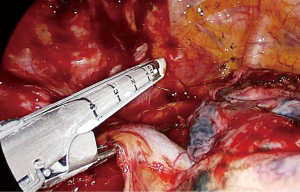

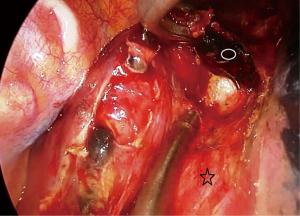

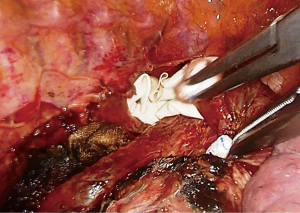

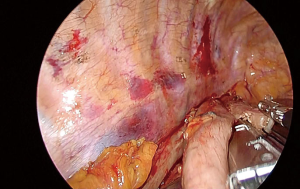

The dissection starts anteriorly and pericardium is identified at the level of the inferior pulmonary vein (Figure 2). Pericardium serves as a guide to lift the subcarinal lymph node laterally and posteriorly while you can gradually free the lymph node from intermediary bronchus and pericardium until carina (Figure 3). If the tumor is below the carina, you can try to move the esophagus using a forceps with a peanut to assess resectability. If the tumor seems resectable, azygos vein can be divided. The mediastinal pleura above azygos vein is opened. A right angle clamp goes around the azygos vein and a 30–45 mm endoscopic vascular stapler divides the vein. The stapler is fully angled to the right side and it is placed from the anterior part of the incision (Figure 4).

Once the azygos vein is divided, the anterior dissection can be advanced posterior to the carina and to the membranous part of the trachea. Anterior to the pericardium, the plane is relatively avascular and can be advanced until you see the contralateral veins. During this dissection lung is retracted anteriorly with a ring forceps at the bottom of the incision. The other instruments are positioned as follows: forceps with peanut at the apex of the incision, camera in the middle and ultrasonic scalpel at the bottom part of the incision over the retracting forceps.

The fatty tissue between hemiazygos vein and esophagus is divided and descending aorta is visualized. Small aortic branches are divided with ultrasonic scalpel and dissection is carried out until we see the left vagus nerve and contralateral pleura/lung. A right angle clamp is passed from anterior to posterior, esophagus is lifted and encircled with a 2 cm thick penrose drain.

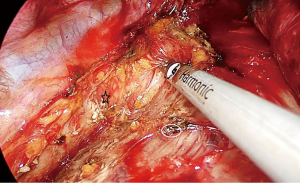

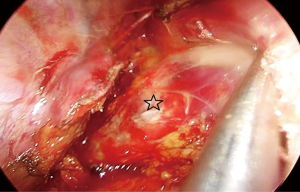

Then the dissection is carried out superiorly and inferiorly. When the penrose drain is retracted anteriorly at the bottom of the incision there is no further need for lung retraction. The posterior side of the esophagus is visualized very clearly and aortic branches are divided (Figure 5). An angled forceps with a peanut can help lift the esophagus to the lateral side opening the plane between left main bronchus and esophagus (Figure 6). If the subcarinal lymph node is very large, at this point the penrose drain is grasped very close to the esophagus with a ring forceps and the ring forceps is pushed inside the chest pulling the esophagus laterally and posteriorly. This move shows the plane between carina, left main bronchus and the subcarinal lymph node (Figure 7). The lymph node is then freed and esophagus is mobilized.

The attachments of the esophagus to the divided azygos vein stumps are divided with ultrasonic scalpel. We can visualize the whole carina, left paratracheal lymph node at this stage. Above the carina, the dissection is carried out close to the esophagus. Vagal nerves are divided. An angled forceps with a peanut is used to bluntly dissect the esophagus posteriorly and anteriorly to the cervical region. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve can be visualized and removed.

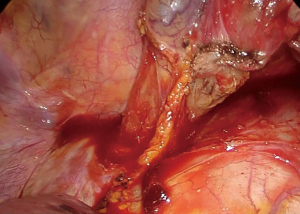

The dissection inferior to the inferior pulmonary vein is performed with an ultrasonic scalped. The pleura is incised along the diaphragmatic crura. Lymph nodes at the contralateral pulmonary ligament can be lifted to the specimen at this stage. The esophagus is lifted laterally and posteriorly to free the attachments to vena cava and pericardium (Figure 8).

If the anastomosis is to be performed in the cervical region, the penrose drain is tied around the esophagus and pushed posteriorly to the neck for easy retrieval (Figure 9).

A single chest tube (28–32 Fr) is placed from the bottom of the incision, aligned inferiorly and advancing to the apex from the paravertebral sulcus adjacent to the stomach conduit.

Peculiarities of intrathoracic gastric interposition and esophagogastric anastomosis through a uniportal incision

The mobilization technique of the esophagus is the same in case of a MI Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. We avoid very high dissection of the esophagus at the apex of the chest. Once intrathoracic esophagus is mobilized, the specimen is pulled to the chest in correct orientation. The stapler line should be facing the lateral wall of the chest. The specimen is grasped and pulled until the apex of the chest. With this maneuver, we make sure that we have adequate length of stomach operation. Usually a 16–20 cm of conduit should be a sufficient length to reach to the apex of the chest.

Once this is checked, the stomach conduit is divided with a 60 mm thick tissue endoscopic stapler at its tip. At this point the tip is once more checked for its length. Then the esophagus is divided 1–2 cm above the azygos vein with a 60 mm thick tissue endoscopic stapler. Staplers are placed from the apex of the incision and angle is applied if necessary. It is important to make sure that nasogastric tube is completely removed at this stage.

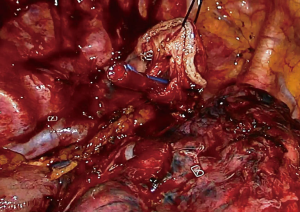

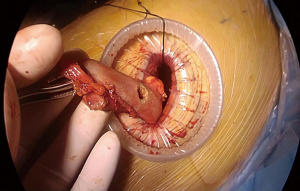

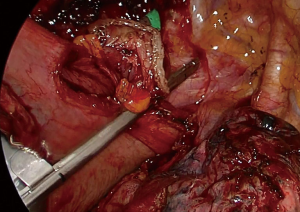

At this stage, anastomosis can be performed (Figure 10). A no.1 silk suture is placed at the stapler line of the esophagus. The suture is retracted from the incision and an opening is made at the medial side of the esophagus. Once the mucosa is opened nasogastric tube is advanced and pushed out of the esophagotomy for 2–3 cm (Figure 11). Then stomach conduit is pulled out of the single port incision in the same orientation. A 6–7 mm gastrotomy is made 3–4 cm distal to the tip of the stomach conduit (Figure 12). Gastrostomy can be placed anterior or posterior depending on the preference of the surgeon. We typically make an anterior gastrotomy. Another no 1 silk suture is placed at the tip of the stomach for retraction. The thicker leg of a 60 mm thick tissue endoscopic stapler is placed inside the stomach. The stapler is advanced inside the chest while applying gentle traction to both silk sutures. Camera is at the apex and stapler is in the middle of the incision. No angle is applied to the stapler. The thin leg of the stapler is advanced inside the esophagus taking the nasogastric tube as a guide. Once both legs are inside the esophagus and stomach, nasogastric tube is completely removed. Edges of esophagus and stomach are aligned equally and stapler is fired to form the posterior side of the anastomosis (Figure 13). The stapler is removed and nasogastric tube is advanced under direct vision. In some cases nasogastric tube can be advanced after completion of the anastomosis. Both silk sutures are lifted inside the chest towards the lateral chest wall. One or two firings of 45–60 mm thick tissue endoscopic stapler complete the esophagogastrostomy (Figure 14). The stapler is frequently fully angled and placed from the apex of the incision. If present omentum is pulled over the stapler line and the stapler line is checked for its contact with membranous part of the trachea. Air is insufflated from the nasogastric tube and the stapler line is checked for leak and integrity.

Discussion

U-VATS for esophageal cancer is becoming possible in the current era of advanced MI thoracic surgery. There is a single report from China, showing that uniportal and multiportal VATS approaches in esophageal cancer are comparable in terms of duration of surgery, amount of bleeding, lymph node yield and leak rates (8). The use of less number of incisions certainly further decreases trauma to the patient who is already undergoing a major gastrointestinal resection. We tried to simplify our technique by adding certain maneuvers which are detailed in the above sections. We used this technique in 18 patients (6 had neoadjuvant and 1 had curative chemoradiation) with no early postoperative leaks and only 1 patient experienced stapler line leak 22 days (was discharged on the 7th postoperative day) after surgery which was healed with drainage. The technique is feasible in patients who underwent chemoradiation, however if severe adhesions exist between aortic arch, left main bronchus and esophagus, a second port at the 8th intercostal space on the posterior axillary line provides better angle and control.

There are several intrathoracic anastomotic techniques. The most commonly applied technique is a circular stapler anastomosis which involves placement of an anvil and circular stapler inside a gastric conduit (4). Although there are several practical versions, the placement of a purse-string suture on the esophagus is technically demanding and sometimes muscular approximation is not perfect (4,9). Semi-stapled anastomosis involves a posterior stapler line, and separate sutures on the anterior part AME (10). Oral anvil placement is also popular, but a 28 anvil is sometimes difficult to pass through the upper esophageal sphincter (11). All of these techniques can be applied through a uniportal approach. Side to side completely stapled anastomosis is safe, fast and easy to perform. It makes a longitudinal stapler line which allows flow of fluids without any retention in a pouch like structure. The long stapler line appears to be a disadvantage, thus utmost attention should be given not to disrupt vascularity of both stomach and esophagus.

In conclusion, U-VATS for esophageal cancer is a demanding technique which needs flexibility in three dimensional thinking and manipulation. It should be performed by experienced esophageal surgeons and following a surgical evolution from multiportal to uniportal VATS (12). Surgeons confident with uniportal approach can perform the procedure, however familiarity with manipulations for posterior mediastinum and esophagus is essential. It is developing and emerging as a new approach and the technique is feasible and certainly future studies will show if it is reproducible and provides a clinical advantage for the patient.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Batirel is a consultant with Johnson and Johnson and receives fees and honoraria.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Luketich JD, Alvelo-Rivera M, Buenaventura PO, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg 2003;238:486-94; discussion 494-5. [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Wang R, Liu S, et al. Refinement of minimally invasive esophagectomy techniques after 15 years of experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:1768-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg 2012;256:95-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pennathur A, Awais O, Luketich JD. Technique of minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:S2159-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batirel HF. Dissection of subcarinal lymph node en bloc with the esophagus. Asvide 2017;4:455. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1772

- Batirel HF. Dissection on the left main bronchus and demonstration of the membranous side of left main bronchus. Asvide 2017;4:456. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1773

- Batirel HF. Technique of intrathoracic linear stapled side to side esophagogastrostomy. Asvide 2017;4:457. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1774

- Guo W, Ma L, Zhang Y, et al. Totally minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with single-utility incision video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for treatment of mid-lower esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:139-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang R, Kang N, Xia W, et al. Thoracoscopic purse string technique for minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:148-51. [PubMed]

- Gorenstein LA, Bessler M, Sonett JR. Intrathoracic linear stapled esophagogastric anastomosis: an alternative to the end to end anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:314-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen NT, Nguyen XM, Masoomi H. Minimally invasive intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis: circular stapler technique with transoral placement of the anvil. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;22:253-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Choong CK, Lim E, et al. A surgeon's case volume of oesophagectomy for cancer strongly influences the operative mortality rate. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:375-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Batirel HF. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery for esophageal cancer. J Vis Surg 2017;3:156.